Highlights from the Major Projects Association event held on 18th May 2016

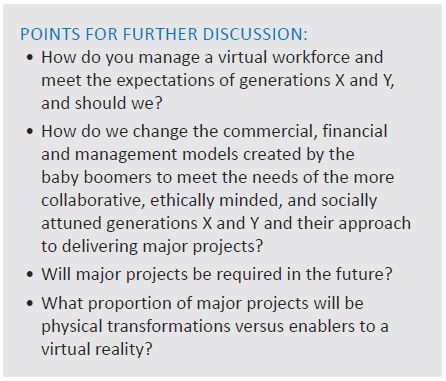

With post-war baby boomers exiting the workforce and the expectation that generation Y (1980 –1995), the Millennials, will shortly make up the largest proportion of the workforce. The event raised the question, ‘How will major projects change when they are led by generations X and Y?’

Far from the perception generated in the press around the ‘forgotten generation X’ (1963–1980) and the ‘lazy Millennials’, the panel considered there was every reason to be optimistic, even energised, by the prospect of major projects being led by generations X and Y, especially given the enviable pipeline of projects we are currently enjoying.

So what can we expect to be different when that happens?

THE COMMUNITY IS THE CLIENT

According to Liane Hartley, the image of a generation attached to their mobile devices as separated from those around them is not accurate – she suggested that generations X and Y are able to collaborate and share ideas like no other generations before.

Whilst seemingly lost in a digital world, it is interesting to speculate what people are actually achieving using the power they have in their pocket.

Despite cultural stories to the contrary, change rarely comes down to an individual, rather from a community coming together around a common goal. In seeking the changes which typically drive major projects, Liane Hartley spoke of the need to embrace a wider spectrum of voices at a local level, recognising the power of ‘small’ change.

Matthew Evans spoke of the Old Oak Common and Park Royal Development Corporation. To ensure they had a wide spectrum of people involved in the master planning of this area of London they crowdsourced across 37 companies and a wide range of citizen groups.

The panel felt there was a real need to find new ways to collaborate more with the end user in the design process, giving them a voice in how major projects are delivered. There is a need for governments to be more responsive and to listen.

Robin Lapish did not believe the public will be willing to continue delivering major projects in the current way. Robin spoke of the NEC suite of contracts as confrontational and adversarial, where signing a contract can be like a declaration of war. There is a need for new commercial and financial models to respond to a more collaborative and less risk-averse approach to delivering major projects, enabling the supply chain to be entrepreneurial in their approach. Robin raised the concept of crowdsource funding as a way to monetise people’s preferences, where people are prepared to pay for what they want.

THE ETHICAL, SOCIAL AND RESPONSIBLE GENERATION

Matthew Evans pointed out that the smartphone we have in our pockets has more computing power than the computer that sent Apollo into space, and we are seeing an explosion of new technologies on the back of that growth in computing power. So how have we not become more productive?

Matthew spoke about the need to focus less on new toys and more on how we use them to create a better world. According to Wired magazine, generation Y is the most ethical, social and responsible generation, very aware of the scarcity of resources, rising population and the ongoing urbanisation of our population. Rather than seeking to control or halt these trends, Millennials are looking for solutions which will not only maintain our standard of living but expect it to improve continually, much as our phones do, without any need to change the hardware.

Matthew spoke about the need to focus less on new toys and more on how we use them to create a better world. According to Wired magazine, generation Y is the most ethical, social and responsible generation, very aware of the scarcity of resources, rising population and the ongoing urbanisation of our population. Rather than seeking to control or halt these trends, Millennials are looking for solutions which will not only maintain our standard of living but expect it to improve continually, much as our phones do, without any need to change the hardware.

THE VIRTUAL MAJOR PROJECT

According to Matthew Evans we are in the foothills of the smart city. We will be living in data-driven cities, where many of our major projects will be as much a technological challenge as a physical reality. Advances in technology far outstrip the speed at which we can build. There is a need for digital flexibility – an ability to change the capability of the hardware we already have, using the data gained around the real needs of the end user.

With the rise in technology-driven projects, major projects may not be so much about boots on the ground as about managing a virtual office. Generations X and Y see work as a function rather than a place to be. With telecommuting rising, you may never step foot in an office and might never meet the team face-to-face. It raises the question of how you manage a major project when there is nobody there. But it is important to note that it should not be technology for technology’s sake. Technology cannot replace human relationships and what is achieved through them; technology needs to enable them, as seen in the rise of social technology.

TECHNOLOGY DOES NOT DESTROY JOBS, IT CHANGES THEM

The way we work and the work we do is rapidly changing. Many of the jobs generations X and Y will do in the future do not exist today. Rather than seeing this as a cause for gloom, the panel felt that generations X and Y will rise to the challenge. Matthew Evans felt that technology does not destroy jobs, it allows people to be upskilled into more interesting employment, where they can refocus on issues they really care about.

To meet this challenge there is a need for continuous learning. As the generations who were sold the idea that they needed to go to university to succeed, the panel questioned the continuing validity of this.

Are universities able to keep up with the rapid level of change? There was a common consensus around the need for a tighter collaboration between educational institutions and the wider community, as seen by companies setting up their own universities and the focus on work-based apprenticeships.

And we can utilise the power of technology to support this. Surgeons are already using virtual reality to learn how to save people’s lives. Will major projects use it to learn how to lay a railway track? As Morgan put it, we can learn as fast as our phones can update.

When challenged with the concept that the Y generation have grown up expecting things for free, Robin Lapish responded by pointing out that Millennials know more than most about money and the risk inherent in economic cycles. But potentially they will measure value differently. As Liane Hartley pointed out, there is an entrepreneurial spirit based on creating money from a social and ethical mindset. The start-up culture, now developing even in larger organisations, is creating a new notion of value that goes beyond money.